News and Reports

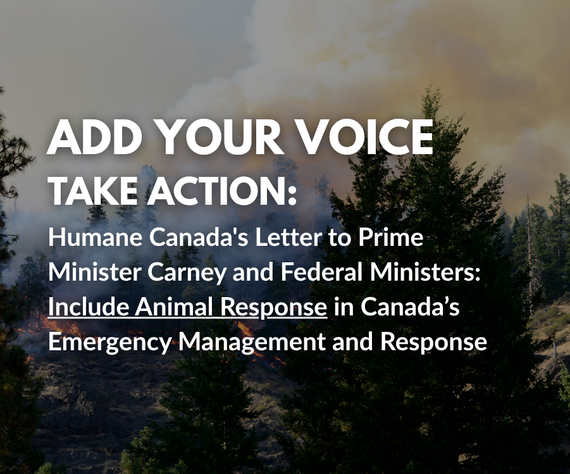

It’s time for animal welfare professionals to have a seat at the emergency planning table

While the worst of this year’s wildfire season is over, the unfortunate certainty is that it will return next year.

Now is the time to prepare for what’s coming and ensure that animals are included in the emergency response in addition to people and property.

Barbara Cartwright, CEO of Humane Canada, says to date, animals have not been integrated into emergency planning in most parts of the country.

That’s no small thing considering more than 60 per cent of homes in Canada have at least one companion animal, and 71 per cent of those owners consider their pets family.

The strength of the human-animal bond was on full display in 2005 during Hurricane Katrina. With no place to go with their pets, people stayed in their homes, ultimately costing many of them their lives.

“They wouldn’t evacuate without their animals,” Cartwright says.

The disaster marked a turning point for emergency planning south of the border. For a while, it also drove some discussion in Canada, but Cartwright says nearly 20 years later, “We haven’t learned much.”

As a result, adequate responses to the needs of animals are often overlooked during the emergency preparedness phase and at the onset of a response. Often, animal response is only considered days and weeks into an emergency, which creates unnecessary challenges for animal welfare providers and first responders trying to manage a dangerous situation.

After the 2023 wildfire in Fox Lake, more than three weeks passed before Deanna Thompson, executive director of Alberta Animal Rescue Crew Society, and her colleagues were called to help with animals left behind in the evacuated community.

“The first responders did their best to help manage and care for the free-roaming dogs, but they made a few big mistakes,” she says.

Food was poured on the roads, which drew animals from their homes, causing massive fights among a large intact dog population. Animals were killed in these fights and by fire trucks and heavy equipment on the roads.

When first responders found starving puppies, they put them all in the same pen until they could get them out of the community. Thompson says it caused a parvovirus outbreak her team had to deal with.

“They didn’t understand proper quarantine protocols. We saw over 35 cases of parvovirus, and I’m sure there were many more.”

Many dogs were taken out of the community without documentation and given away. When Thompson and her team arrived, the community was angry their pets were stolen.

“There’s a lot of things that could have been done differently and a lot of advice that could have been given in the early days of this disaster — and others,” she says.

Deanna Thompson, Executive Director Alberta Animal Rescue Crew Society If we had a professional with companion animal experience at the table from the beginning, it would be extremely beneficial in reducing issues and suffering.

No one needs to tell the Nova Scotia SPCA that.

When devastating wildfires forced thousands of people and pets from their homes in 2023, the organization had never responded to anything on that scale.

The day of the evacuation order, executive team members handed out water, food, and litter boxes to evacuated families who’d pulled off the highway to watch the fire.

“This was unheard of in Nova Scotia. People assumed they would get back home before the end of the night,” says Marni Tuttle, the SPCA’s executive director of advancement.

“It wasn’t long before they realized that wouldn’t be happening.”

The SPCA started boarding animals for families that first night. Once fire crews learned the SPCA was on the ground, several staff members were brought to a house in immediate danger where animals could be heard inside. Firefighters held off the flames while SPCA staff rescued nearly 40 animals.

Staff had to find spots for those animals to stay, as well as a pot-bellied pig and several dogs that couldn’t go into traditional boarding. Thirty-six hours in, the SPCA partnered with the emergency management centre and actively evacuated animals stuck in homes behind the lines. In all, Tuttle says they boarded more than 240 animals.

In addition to the wildfires, the SPCA had to respond to the effects of Hurricane Fiona in September 2022, deadly flooding in the summer of 2023, Hurricane Lee in the fall of 2023 and a massive multi-day snowstorm in the winter of 2024 that left parts of the province in a state of emergency.

Responding to so many extreme weather events in 17 months was challenging, and many lessons were learned. But they’re not being used to plan for the next disaster. Tuttle says they’d like to partner with the government and other organizations to better respond, but they’re not at the emergency planning table.

Instead, they’re still lobbying for a seat and sharing their experiences, making clear what worked and what the challenges were.

“We can make all the plans we want, but what we’ve learned is that if we’re not integrated and connected, we’re not going to be very effective,” Tuttle says.

It’s still widely accepted that human interests should trump animals at all costs, despite the toll that approach can take on animal welfare professionals and owners. Tuttle’s seen first-hand how draining their disaster response has been on staff. That’s mainly due to the lack of integration that’s left them scrambling when the need arises.

What eats at Thompson is the anxiety and invisible suffering animals caught up in disasters experience.

“So many animals were lost in the Fort Mac fires in 2016. We went into one house with 25 dead birds because we didn't get there in time.”

It wasn’t that it wasn’t safe — the time lag was due to animal welfare professionals trying to get into the community.

“(Disaster response) puts a significant strain on the team because we also have so many animals that require care throughout the year,” says Liza Sunley, CEO of the Edmonton Humane Society and vice-chair of Humane Canada.

“When these sorts of emergencies come up, we’ve thankfully been able to help at the time, but it does add significant pressure to an already stressed sector.”

The situation isn’t sustainable, however, as shelters receive no government funding, and are in a perfect storm. They’re full, staff is exhausted, and donations are down.

At a time when climate change is making emergencies more common, shelters are limited in their ability to respond to them.

“Governments have got to wake up,” Cartwright says.

“They have to realize the important role animal welfare professionals play and make this central to their emergency response planning while also putting the resources in place to support it.”